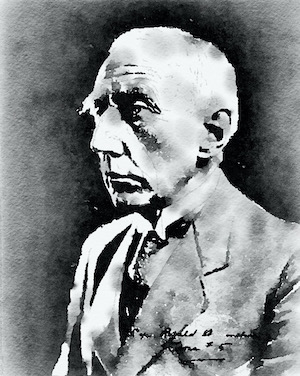

Norwegian explorer Roald Engelbregt Gravning Amundsen was the first man to navigate the Northwest Passage, reach the South Pole, and fly over the North Pole.

While Amundsen was born into a family of shipowners and captains, his mother wanted him to become a doctor. That always seems to have been an unlikely prospect.

He had read Sir John Franklin's narratives of his Arctic expeditions and other accounts of polar exploration as a boy and found them fascinating.

Although Amundsen spent two years studying medicine at the University of Christiania in Oslo, he dropped his studies when his mother died. He went to sea, working as a seaman in Arctic waters.

He began his career as a polar explorer as the first mate on Adrien de Gerlache's Belgian Antarctic Expedition (1897–1899).

By accident or design, the Belgica was trapped in sea ice west of the Antarctic Peninsula and became the first vessel to overwinter in Antarctic waters. The expedition's American doctor, Frederick Cook, probably saved them from scurvy by hunting and feeding fresh meat to the crew.

After he returned from the Antarctic, Amundsen obtained his master's certificate. In his first expedition as the leader, Amundsen took a party of six on a three-year traverse of the Northwest Passage between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans in the Gjøa, a 45-ton shallow draft fishing smack with a thirteen-horsepower single-screw paraffin engine.

Over nineteen months spread across two winters in Gjøa Haven on King William Island, Amundsen's party attempted to locate the North Magnetic Pole. They found that the magnetic pole is not stationary but remains in continual movement. Interactions with the local Netsilik Inuit people taught the party survival skills, which proved invaluable in later expeditions.

From Gjoa Haven, the party sailed west, cleared the Canadian Arctic Archipelago in mid-August 1905. After another Arctic winter in northern Alaska, Amundsen travelled overland to Nome. He continued for another eight hundred kilometres to the nearest telegraph station in Eagle, further around the Pacific coast, to report his successful transit of the Northwest Passage.

Amundsen then retraced his tracks, becoming the first person to navigate the long-sought waterway in both directions. He was back in Oslo in November 1906, after an absence of almost three-and-a-half years.

In his next Arctic project, Amundsen planned to use Fridtjof Nansen's Fram to drift towards the North Pole and complete the journey by sledge. However, when Robert Peary claimed to have reached the Pole in 1909, Amundsen switched his ambitions to the Antarctic.

The Fram left Norway in June 1910, reached Antarctica the following January 1911 and established a camp at the Bay of Whales. After establishing a series of supply depots on the Ross Ice Shelf and overwintering, Amundsen set out for the South Pole with a party of five in October. After a two-month dash using skis and dog sledges, they reached the South Pole on 14 December 1911.

Robert Falcon Scott's ill-fated expedition arrived thirty-five days. The British party used horses and manpower rather than dogs to haul their supplies across the ice.

While the First World War (1914–18) halted polar exploration, Amundsen used the considerable personal fortune he had acquired to build a polar ship (the Maud).

Inspired by Fridtjof Nansen's earlier expedition in the Fram, Amundsen planned to drift across the North Pole from Asia to North America. He intended to sail along the Siberian coast and enter the ice further north and east than Nansen had.

While the ship was unable to penetrate the polar ice, when Amundsen reached Alaska, he had sailed through the Northeast Passage, emulating Nils Nordenskiöld's 1878-1879 traverse of the same waters.

The experience convinced Amundsen that the air offered the best prospects for Arctic exploration. He divided the expedition team in two, planning to overwinter and prepare to fly over the pole in 1923.

Meanwhile, the Maud would resume the original plan to drift over the North Pole in the ice. The ship spent three years in the ice east of the New Siberian Islands without reaching the North Pole before Amundsen's creditors seized it to service his mounting debt.

The 1923 attempt to fly from Alaska to Spitsbergen across the North Pole failed when the aircraft was damaged. After abandoning the journey. Amundsen spent 1924 on a lecture tour in the United States.

A 1925 attempt to overfly the Pole in two Dornier flying boats reached 87° 44′ before the aircraft forced to land a few kilometres apart. It was the northernmost latitude reached by an aeroplane. After the crews managed to reunite, with one aircraft damaged.

Amundsen's team spent more than three weeks preparing an airstrip, shovelling six hundred tons of ice on limited rations. The serviceable aircraft barely succeeded in getting off the ice, but the party of six managed to return to base.

The following year in the airship Norge, piloted by Italian Colonel Umberto Nobile, a second attempt left Spitsbergen on 11 May. Amundsen, Nobile and the American Lincoln Ellsworth landed in Teller, Alaska, two days later., having circled the Pole twice en route

The American Robert E. Byrd claimed to have flown to and from the North Pole from Spitsbergen on a fifteen and a half hour flight two days before Amundsen's airship departed. However, subsequent evidence suggests an oil leak forced Byrd to turned back around 240 kilometres short of the Pole.

Later evidence has also thrown Peary's claim to have reached the Pole into doubt. So it seems Amundsen, Nobile, and Ellsworth were the first people with a verified claim to have reached the Pole by air or land.

Two years after the North Pole flight, Amundsen disappeared on an aerial search for Nobile, whose new airship Italia had gone missing on another polar flight.

Although Nobile was rescued, Amundsen's flying boat is presumed to have crashed in the Barents Sea. The Norwegian government called off the search for Amundsen and his crew in September 1928.

Amundsen's contribution to geological and geographical knowledge was substantial. His popular accounts of his expeditions include The South Pole (1912), First Crossing of the Polar Sea and My Life as an Explorer (1927).

Sources:

Felipe Fernandez-Armesto (ed.) The Times Atlas of World Exploration

Chambers Biographical Dictionary

Encyclopedia Britannica

Dear and Peter Kemp (eds), The Oxford Companion to Ships and the Sea

Wikipedia