Although he was, notionally, Italian, explorer Alessandro (a.k.a. Alexandro, usually modernised to Alejandro) Malaspina (1754 – 1810) spent most of his life as an officer in the Spanish navy, undertaking two significant voyages. The first, a circumnavigation (September 1786 to May 1788) was a commercial venture on behalf of the Royal Philippines Company; the second, a scientific expedition, explored and mapped much of America's west coast from Cape Horn to the Gulf of Alaska, then crossed the Pacific to Guam and the Philippines, before moving on to New Zealand, Australia, and Tonga. The scientific data collected along the way surpassed that of Cook, but changed political circumstances in Spain saw Malaspina jailed after his return. Publication of the reports and displays of the collections he had brought back were prohibited and, as a result, the expedition and its findings remained obscure until the late 20th century.

While Malaspina's expedition set out to equal or surpass the scientific successes of its English and French predecessors, and there is no doubt that it succe3eded in doing so, history intervened and the voyages of Cook, La Pérouse, and Bougainville continue to dominate historical scholarship and the historical imagination.

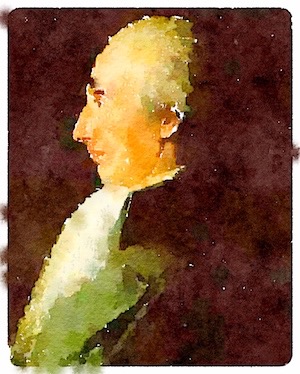

Born into an influential Tuscan family on 5 November 1754 (his father Carlo Morela Malaspina was marquess of Mulazzo while his mother's uncle was the viceroy of Sicily) Malaspina grew up in Palermo with his great-uncle, before moving to Rome to study at Pio Clementino College (1765 to 1773). After a year as a member of the Order of Malta, where he learned the basics of sailing, then followed his uncle to Spain in 1774 and joined the Spanish Royal Naval Academy in Cadiz as a sailor guard.

Between 1774 and 1786 Malaspina took part in naval operations around the Mediterranean, including the expedition to relieve the Moroccan siege of Melilla, the siege of Algiers, the Battle of Cape Santa Maria and the Great Siege of Gibraltar, as well as three missions to the Philippines.

While he was suspected of heresy and denounced to the Spanish Inquisition in 1782, he was not apprehended and went on to serve as second-in-command aboard the frigate Asunción on his second voyage to the Philippines. Back in Spain in 1785, Malaspina took part in hydrographic surveys before a third voyage to the Philippines, in command of the frigate Astrea, on behalf of the Royal Philippines Company

The mission, which ended up as a circumnavigation and planted the seeds for his most notable expedition.

Where his previous journeys to the east had gone via the Cape of Good Hope in both directions, the third voyage rounded Cape Horn and called at Concepción in Chile, where he met with the Irish-born military governor, Ambrosio O'Higgins.

Higgins had recommended a Spain expedition to the Pacific along the same lines as earlier British and French expeditions, following the La Pérouse expedition's visit to Concepcion in March 1786, and would presumably have discussed the notion with Malaspina while the Astrea was at Concepcion.

When the Astrea returned to Spain, Malaspina and another frigate captain, José de Bustamante, submitted a proposal for a political and scientific expedition along the same lines as Higgins's proposal, one that would visit Spanish possessions in the Americas and Asia and assess their populations and resources.

The plan was accepted on 14 October 1788, thanks, in part, to the Higgins memorandum and to the news that the Russians were preparing an expedition to the North Pacific, which would probably attempt to lay claim to the territory around Nootka Sound also claimed by Spain.

The expedition was to sail under the dual command of Malaspina and Bustamante, and while it became known as Malaspina's voyage, he never considered Bustamante as his subordinate although Bustamante acknowledged Malaspina as the expedition's chief.

The expedition sailed from Cádiz on 30 July 1789 on two frigates, purpose-built under Malaspina's direction, named Descubierta (Discovery) and Atrevida (Daring or Bold), names deliberately chosen to echo Cook's Discovery and Resolution. Both were thirty-six metres long, displacing 306 tonnes and were launched together on 8 April 1789.

Like their French and British predecessors, the two ships carried some of the leading scientists of the day, including the Spaniard Antonio Pineda, Frenchman Luis Neé and experts in the fields of mineralogy and medicine, Czech botanist Thaddeus Haenke missed the departure and joined but caught them up in Santiago de Chile after crossing South America from Montevideo by land.

The two ships arrived off the coast of Uruguay on 20 September, called in at Montevideo and Buenos Aires to investigate the political situation and resources of the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata. After rounding Cape Horn, Bustamante mapped the coast of Chile, while Malaspina headed to Juan Fernández to resolve conflicting details about their location. The two reunited at Callao, the port for Lima, made another investigation of the Viceroyalty of Peru, then continued north to Acapulco to repeat the exercise for the Viceroyalty of New Spain.

Along the way, a stop in Panama harbour saw Malaspina ponder the possibility of a canal across the isthmus a shortcut linking the Atlantic and Pacific oceans.

When the expedition arrived in Mexico, the leaders received dispatches from Spain which prompted a change of plans. The original intention had been to cross the Pacific via Hawaii and then loop back around from Kamchatka to America's Pacific Northwest, filling in the gaps from Cook's third voyage. Now, following reports that the long-sought Northwest Passage had been found, Malaspina was redirected to Yakutat Bay at the northern end of modern Alaska's panhandle (fn) which was reputed to be the passage's Pacific outlet.

(fn: The 29-kilometre inlet at Yakutat Bay takes its name from the local indigenous Tlingit people, rendered as "Jacootat" and "Yacootat" by the Russian Yuri Lisianski in 1805. However, it appears on earlier charts under many different names. The waterway is Cook's Bering Bay, La Pérouse's Baie de Monti and Nathaniel Portlock's Admiralty Bay. It appeared on some Spanish charts as Almirantazgo and was also known as Port Mulgrave when Malaspina and Bustamante sailed into it. It was subsequently the site of a Russian colony variously known as New Russia, Yakutat Colony, or Slavorossiya after 1795.)

The rumoured passage was, however, only an inlet. Malaspina named the waterway at the head of the inlet Puerto del Desengano (Disenchantment Bay) and turned his attention to

a careful surveyed the Alaskan coast west to Prince William Sound and ethnographic and linguistic studies of the local Tlingit people.

The Spanish scholars carried out a detailed study of the tribe, covering social customs, the language, economic activity, modes of warfare and burial practices, while the expedition's artists produced portraits, landscapes and scenes of daily life. Botanist Luis Née collected and described numerous new plants.

When they were done, knowing Cook had covered the coast west of Prince William Sound without finding the passage, Malaspina turned his attention to the Spanish outpost at Vancouver Island's Nootka Sound, where a month-long stay produced further extensive ethnographic studies of the Nuu-chah-nulth people. Malaspina's ability to deliver generous gifts from well-stocked ships saw relations with the local people improve significantly, which, in turn, strengthened the Spanish claim to Nootka Sound, which remained in question after the Nootka Crisis and had not yet been resolved in the subsequent Nootka Conventions.

The Spanish government needed the Nootka to deliver a formal agreement that the Spanish outpost occupied land that had been freely and legally ceded to Spain, and Malaspina was able to acquire precisely what was needed. Weeks of negotiations produced a pact that had a significant influence on the outcome of the Nootka Convention.

On the scientific front, astronomical observations fixed the location of Nootka Sound and provided the opportunity to calibrate the expedition's chronometers. The hydrographers surveyed and charted Nootka Sound, investigated unexplored channels and linked their findings to Cook's baseline. Botanical studies included an attempt to make an anti-scorbutic beer out of conifer needles while the two ships took on wood and water.

From Nootka Sound Malaspina and Bustamante called in at the Spanish mission settlement at Monterey on their way back to Mexico. While they were there, Malaspina assigned two of his officers, Dionisio Alcalá Galiano and Cayetano Valdés y Flores two schooners (goletas) and the task of conducting more detailed explorations of the Straits of Juan de Fuca and Georgia around the current border between the United States and Canada. Two local pilots from San Blas were to have commanded the vessels, but Malaspina's officers replaced them.

From Mexico, the expedition crossed the Pacific, with a brief stopover at Guam before a lengthy stay in the Philippines. Malaspina set about his regular business in Manila while Bustamante visited Portuguese Macau in the Atrevida.

When Bustamante returned, the expedition sailed to New Zealand, where they explored Doubtful Sound at the southern end of the South Island before crossing to Sydney.

During the expedition’s stay in March and April 1793, Thaddäus Haenke carried out observations and made botanical collections. Twelve drawings by members of the expedition provide a valuable record of the five-year-old settlement, including the only contemporary depictions of the convicts from the period.

There were other reasons for including the settlement in Malaspina's itinerary.

A September 1788 memorandum by naval officer Francisco Muñoz y San Clemente had pointed out the dangers the new colony posed as a base for naval operations in wartime and a source of contraband commerce in times of peace. Malaspina's confidential report echoed Muñoz, pointing out the danger an easy two or three month crossing through healthy climates posed to the defenceless coasts of Spanish America.

However, while Malaspina recognised the strategic threats in a time of war, he also drew attention to the commercial opportunities for trading in food and livestock from Chile across the Pacific, and the development of a viable trade route between South America and the Philippines.

From Sydney, the two frigates tacked back across the Pacific, spent a month at Vava'u, Tonga's northern archipelago on the way to Callao and on to Talcahuanco in Chile. They stopped to chart southern Chile's fjords before the expedition rounded Cape Horn.

In the South Atlantic, they surveyed the Falkland Islands (in Spanish, the Islas Malvinas) and the coast of Patagonia before another stop at Montevideo.

The expedition arrived back in Cadiz on 21 September 1794, after an absence of nearly five and a half years, having amassed an unprecedented trove of knowledge.

His cartographers, botanists, naturalists and astronomers had enjoyed almost total freedom of action that allowed them to accumulate a collection of new maps, sketches and collections of plant species and mineral specimens at each stop along the way (and, as we have seen, there were numerous stops).

Along the way, Malaspina had charted America's western coast with unprecedented precision (a significant achievement, given Cook's presence among the predecessors). He measured the height of Alaska's Mount Saint Elias, explored gigantic glaciers, suggested a feasible route for a canal across the Isthmus of Panama, with preliminary plans for the project and completed the first significant voyage where scurvy was, effectively, absent. (fn)

(fn: A single outbreak on the fifty-six-day passage from Mexico to Guam had seen five sailors exhibit symptoms of scurvy. One case was described as severe. Three days at Guam saw all five return to full health.

Where Cook made significant progress in preventing the disease, many of his measures were, basically, ineffective and he had failed to recognise the critical role of citrus fruit in maintaining the levels of ascorbic acid (Vitamin C). Other British captains, Including George Vancouver, found his accomplishment impossible to replicate.

While the antiscorbutic properties of oranges, lemons and limes had been known since the middle of the 18th century, it was not possible to store fruit or fruit juice for long periods without losing the essential acid. Spain's extensive empire and the expedition's numerous ports of call meant the ships' crews could acquire abundant supplies of fresh fruit, and aMalaspina's medical officer, Pedro González, ensured that they did.)

Taken all together the mass of information that the expedition provided could have given the authorities in Madrid with a better understanding of the Spanish empire as a whole, as well as the issues that related to each component of the greater whole, but it was not to be.

At first, however, the prospects for reform appeared promising. Charles III had died while the expedition was away, but his successor, Charles IV and Prime Minister Manuel de Godoy met Malaspina at the Escorial in December 1794, and Malaspina was promoted to fleet-brigadier in March 1795

Malaspina's confidential report (Viaje político-científico alrededor del Mundo, 1794), developed his views about the management of the Empire and criticised existing practices in an old-fashioned and stagnant colonial regime. He advised greater autonomy for the colonies, working towards a confederation enjoying trade agreements, greater religious tolerance and a reformed administrative structure.

Unfortunately, Malaspina delivered his report to the wrong prime minister. The reception might have been different if Godoy's predecessor, the Count of Aranda (fn) was still in office.

(fn: Spanish statesman and diplomat Don Pedro Pablo Abarca de Bolea y Jiménez de Urrea, 10th Count of Aranda (1718 – 1798) joined the Spanish Army after studying at the seminary of Bologna and the Military School of Parma. Severely wounded and left for dead on a battlefield during the War of the Austrian Succession, he travelled through Europe after he recovered, He studied the Prussian Army and met key figures in the Encyclopédie and Enlightenment movements, including Diderot, Voltaire and D'Alembert during a lengthy stay in Paris. After spells as ambassador to Portugal and Poland, and a variety of military and administrative positions he went on to promote liberal reforms until his political enemies at the Spanish court managed to have him sidelined as ambassador to France (1773 – 1787). While in Paris, he drafted a proposal to transform Spain's American empire into a Commonwealth of three independent kingdoms with a member of the royal family on each throne while the Spanish king remained as the overall Emperor.

He returned to Spain in 1787, and at the start of 1792 replaced the Count of Floridablanca as prime minister. When Louis XVI was imprisoned in France in August, Aranda's Enlightenment leanings seemed incompatible with the total war against revolutionary France that was being advocated in Court circles. Manuel Godoy, therefore, replaced him in November. He fell out with the new prime minister after the Spanish army lost Roussillon in November 1794, and was subsequently arrested and confined to his estates in Aragon where he died in enforced retirement.)

Given Aranda's earlier proposal of a Commonwealth dividing Spain's existing American empire into three independent kingdoms (fn) with a Spanish infante on the throne of each while the king retained the title of Emperor, Malaspina's recommendation would probably have gone down well.

(fn: Peru, Tierra Firme, combining New Granada and Venezuela, and Mexico)

However, Manuel de Godoy (fn) who had replaced Aranda two years earlier had no interest in liberal reform.

(fn: Over two terms as prime minister (1792 — 1797 and 1801 — 1808 Spanish statesman Manuel de Godoy, Duke of Alcudia (1767—1851) received many titles and managed to enjoy royal patronage and retain power despite multiple disasters that would have brought most other leaders undone.

The youngest child of poor but noble parents, Godoy moved to Madrid in 1784 to join the royal bodyguard, where his singing, guitar playing, intelligence and audacity allegedly caught the eye of the future Queen María Luisa as well as her husband's trust. When Charles IV succeeded to the throne, Godoy, raced upwards through the ranks. Prime minister Floridablanca accused him of an adulterous relationship with the Queen in 1791, but his days were numbered, and Godoy deposed his successor Aranda to become prime minister in 1792. While he led Spain through a series of disasters, reformists lost all faith in his political credentials, the Church and much of the upper nobility were hostile, and the general population ended up in open revolt.

However, it took the intrigues around the French invasion of 1808, when stories that Godoy had sold Spain to Napoleon to bring about his downfall.

Charles had Godoy imprisoned, and confiscated his property but could only end the uprising and save his minister's life by abdicating in favour of his son Ferdinand VII. That failed to solve the crisis, and in the end, Napoleon had Charles and Ferdinand hand him the Spanish crown in exchange for generous pensions for the exiled royal family and guarantees of Spain's territorial and religious integrity for Spain.

Godoy and his family spent the rest of the Napoleonic era in France, with the exiled ex-King and Queen, before moving to Rome in July 1812 as events played out elsewhere.

Ferdinand VII was restored to the Spanish throne in April 1814 after six years in French exile but refused permission for his parents or Godoy to return to Spain. The refusal continued after Napoleon's final defeat at Waterloo, with Ferdinand VII ensuring that Godoy did not receive a state pension from Spain, though he had better luck after he moved to Paris in 1832, where his straitened circumstances saw French king Louis Philippe grant him a modest pension. Although he was finally authorised to return to Spain in 1844 and had part of his confiscated property returned and some of his titles restored in 1847, Godoy remained in France. He died in Paris in 1851 and was buried there.)

Malaspina made predictable recommendations, suggesting greater autonomy for the colonies and a free trade arrangement that would enrich them without damaging their political relationship with Spain. He was still pushing his proposals in September 1795, but in a court paralysed by fear of political change, an environment where reformist notions were regarded as uncomfortably close to revolutionary ideology and, therefore, incendiary and treasonous, continuing to do so was fraught with danger.

Malaspina may or may not have been part of an actual conspiracy to overthrow Godoy, but when he was arrested on November 23 on charges plotting against the crown that was immaterial.

There was a trial in April 1796, a sentence ten years' imprisonment at an isolated fortress at la Coruña, and a royal decree stripping Malaspina of his newly acquired rank. The sentence brought work on the materials his expedition had gathered to a halt, though Malaspina managed to compose literary reviews and essays on economics and aesthetics, before he was released, as a result of pressure from Napoleon, at the end of 1802.

However, he could not remain in Spain. Malaspina returned to his native land and settled in Pontremoli in the upper valley of the River Magra, forty kilometres northeast of the coastal city of La Spezia, comfortably close to his birthplace and his family's Tuscan estates.

The combination of Malaspina's fall from grace and financial restrictions imposed in the course of Spain's conflict with revolutionary France meant Malaspina's seven-volume account of his expedition remained unpublished until the late 19th century, although a Russian translation appeared between 1824 and 1827. (fn)

(fn: The Russian ambassador in Madrid had obtained a copy of Malaspina’s journal in 1806, and Admiral Adam von Krusenstern's translation appeared in successive issues of the Russian Admiralty's official journal between 1824 and 1827. Von Krusenstern had produced a Russian translation of astronomer José Espinosa y Tello's observations in 1815).

The majority of the documents relating to Malaspina's expedition remain scattered in various archives, and a significant number have disappeared. Many that have survived are in draft, semi-edited form, and while there was some contemporary publication (fn), it took two hundred years for the bulk of the expedition's records to see the light of day.

(fn: Notes made by botanist, Luis Neé at Port Jackson in 1793 were published in 1800. Dionisio Alcalá Galiano’s journal of his detailed explorations of the Straits of Juan de Fuca and Georgia as part of the expedition appeared in 1802, but all references to Malaspina were excised.

A two-volume work covering José Espinosa y Tello's astronomical and geodesic observations and an abbreviated narrative of the voyage appeared in 1809, with a Russian translation six years later.

The Atrevida's second-in-command, Francisco Xavier de Viana's journal was published in Montevideo in 1849, while Bustamante’s journal appeareded in 1868 in the official journal of the Directorate of Hydrography in 1868.

An abbreviated account of the expedition, consisting mostly of Malaspina's journal, was published by Pedro de Novo y Colson in Madrid in 1885.)

In a way, given the circumstances and the sheer volume of data, that time lapse is unsurprising. Madrid's Naval Museum, for instance, has more than three hundred log books and journals from the expedition, four hundred and fifty albums of astronomical observations, one and a half thousand hydrographic reports, more than one hundred and eighty charts, three hundred and sixty-one sketches of coastal elevations, and more than eight hundred botanical and ethnographical drawings. Add to that the sixteen thousand botanical specimens Neé collected for the Real Jardin Botanico, and you end up with what may well amount to the most significant accumulation of scientific materials the eighteenth-century world had seen.

Some four thousand documents manuscripts relating to the expedition were catalogued between 1989 and 1994, and the definitive account of the expedition finally appeared in nine volumes published by the Museo Naval and Ministerio de Defensa between 1987 and 1999.

Back in his homeland, Malaspina involved himself with local politics. In December 1803 he organised a cordon sanitaire to quarantine Napoleon's Italian Republic from a yellow fever epidemic in Livorno, and he received titles and honours from the Kingdom of Italy and the Regent of Etruria before the first symptoms of an incurable disease appeared in 1807. He died at Pontremoli, near his birthplace, in April 1810.

Sources: Felipe Fernandez Armesto, Pathfinders: A Global History of Exploration; http://www.imalaspina.com/en/great-figures/article/alessandro-malaspina.html; Carlos Martinez Shaw, Terra Australis - The Spanish Quest in John Hardy and Alan Frost (eds) Studies from Terra Australis to Australia;