Monday, 19 April 2010

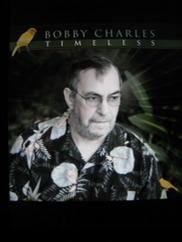

The title of Bobby Charles latest, and presumably last, album says it all, really.

Most of the material on Timeless would have fitted equally well on 1972s Bobby Charles or any of the handful of albums he released over the intervening twenty-eight years.

Since we're only talking a total of eight releases, with a bit of duplication along the way, Charles was never the most prolific of writers, but when you take a glance at the titles in his back catalogue, it's a definite case of quality over quantity.

Ain't Got No Home, Before I Grow Too Old, (I Don't Want To Love You) But I Do, I'm (Just) That Way, Jealous Kind, See You Later Alligator, Small Town Talk, Tennessee Blues, Walking To New Orleans and Why Are People Like That all occupy prominent places in Hughesy's personal music iconography, though that's largely due to a familiarity with covers by The Band, Doug Sahm, The Black Sorrows, and a handful of others including Clarence "Frogman" Henry, Fats Domino and Bill Haley & The Comets.

If you're familiar with them, or if you've already picked up on Bobby Charles, you know exactly what's on offer here, from the down to earth down home feel, to the casual conversational vocal tone and healthy serves of Mac Rebennack (Dr John) and Sonny Landreth in the background. Rebennack's production hits all the right notes, while his keyboards and Landreth's guitar add the punctuation and keep things flowing at the same time.

You're never going to get great philosophical statements in a title like Happy Birthday Fats Domino or the closing Happy Halloween, which uses the same tune. Tunes, of course, aren't exactly what Charles is about, and as the brass and the vocal chorus runs through the bouncy second-line playout to Fats Domino, that New Orleans feel is the essence of the man and his music.

That's not to suggest the man won't philosophise at all. There's a bit of it in Where Did All The Love Go, which is a good question, though predictably Charles doesn't come up with anything too deep and meaningful to sit on top of a comfortable groove apart from noticing it’s gone and wondering which way it went. Nickels, Dimes and Dollars works through the monetary units to enumerate the financial implications of the narrator's heartache, a dollar for every time I holler your name would, in other words, make him a rich man indeed. Like all Charles' work it's straightforward stuff but there's a warmth there that few other artists can generate.

Clash of Cultures, rather than coming out to talk about big philosophical issues, brings it down to me and you which you can read as dealing with a relationship or society as a whole. The highlight of the album is Little Town Tramp, a successor to Small Town Talk, with Charles reflecting on the girl's downfall over some understated B3 from Rebennack. Tasty.

There's a reflective tone running through much of the album, Nobody's Fault But My Own, for example, says it all in the title and makes no bones about it in the lyrics and while the remade Before I Grow Too Old rolls along pleasantly enough it's more up tempo with greater urgency than the '72 version (and most of the covers) suggesting Charles knew he didn't have a lot of time left, and states his intentions without regrets or second thoughts. Sort of that’s the way it is podjo, so this is what I'm gonna have to do.

There's some lovely understated mariachi brass running through Old Mexico, and lyrics that aren't a long way away from those of Down South In New Orleans, and while Rollin’ Round Heaven gets a slightly harder gospel-tinged treatment there's nothing much different about Charles' vocal delivery. When Love Turns To Hate is pretty much as you'd expect it, and if you'd expect a title like Take Back My Country to be a rousing call to arms, and the lyric line seems to have a dig at Sarah Palin, that vocal style isn't going to be storming the barricades any time soon.

After the lingering slide note that begins the penultimate You'll Always Live Inside of Me, Landreth's wonderfully understated guitar work through the rest of the track is one of the instrumental highlights of the album (along with Rebennack's keys on Little Town Tramp). It's the same sort of understated heart-searing you find, for instance in some of Ry Cooder's best work.

As suggested earlier, fans of Charles' work will be happy to know it's a case of more of the same, and for fans of straight ahead uncluttered down home music who aren't familiar with the man's work Timeless is well worth investigating.