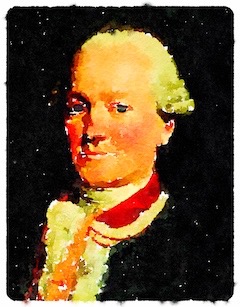

French navigator Jean-François de Galaup, Comte de La Pérouse (1741-1788) is best known for his long voyage, most of which was devoted to the northern Pacific, covering the north-west coast of America, Asia's north-eastern coast and the La Pérouse Strait (a.k.a. Sōya Strait, between Russian Sakhalin and the Japanese island of Hokkaidō). After his two ships left Botany Bay on 10 March 1788, they disappeared without trace until the wreckage was found off the coast of Vanikoro, north of New Caledonia almost forty years later.

While the expedition investigated both the North and the South Pacific, from north of Japan to Botany Bay, his explorations off the Asian mainland in the Gulf of Sakhalin and along the Kurile island chain did something to resolve unanswered questions from the voyage of Dutchman Maarten Gerritszoon Vries in 1643.

La Pérouse was born in Guo near Albi in southern France, joined the French navy at the age of fifteen. While serving in the Formidable off Belle-Isle at the Battle of Quiberon Bay in November 1759, he was wounded, captured and eventually repatriated. When he resumed sea duties, he worked his way through the ranks, perfected his navigational and pursued an interest in oceanography before distinguishing himself in the war against Britain (1778—83). His campaign against the British in Hudson Bay in August 1782 was a success, and he had the decency to leave the vanquished settlers enough arms and provisions to preserve themselves through the next winter.

In 1783, the French government resolved to send an expedition to the Pacific to enhance their national prestige by completing the work Cook and Bougainville had started, and in particular to explore the passages in the Bering Sea. Louis XVI was involved in drafting a comprehensive plan, which included investigations in the South Atlantic and South Pacific covering New Holland and New Zealand, New Caledonia's west coast, which Cook had not seen, Tahiti, the Marquesas and Hawaii, America's northwest coast and waters north of Japan which Cook had not reached..

The instructions were drawn up by Jean-Nicolas Buache de la Neuville, nephew of Philippe Buache and “premier géographe du Roi,.' Royal support ensured the expedition that sailed Brest on 1 August 1785 was better equipped than any other eighteenth-century voyage of the century, except, perhaps Malaspina's subsequent expedition, which also enjoyed lavish royal patronage.

When La Pérouse in the Astrolabe, accompanied by Paul-Antoine de Langle in the Boussole, set sail, making for Brazil. The project had set the shaky French treasury back a staggering one million livres.

From Rio de Janeiro, the expedition rounded Cape Horn on 1 February 1786, spent three weeks refitted in Chile, and proceeded to Cook's Sandwich Islands via Easter Island rather than Tahiti, working on the assumption that the island was already well known. Looking to reach the American coastline in high summer, he made landfall at Maui at the end of May and sighted Mount St Elias on the corner of the border between Canada's Yukon and the Alaskan panhandle on 24 June. From there, he turned south exploring and surveying the coast, searching, as directed, for a waterway into the interior. A month investigating the inlets and channels of Lituya Bay)in Alaska, was enough to convince him that the task was hopeless. He tracked south as far as Monterey in California, where he stopped for a ten-day refit on 14 September.

From there, he crossed the Pacific on a course designed to avoid the Manila Galleon's track, discovered uncharted islands along the way, and made lengthy stays at Macao and Manila before turning north to survey the coastline north of Korea on 10 April 1787.

Foul weather off the Pescadores forced him to the east of Taiwan, passing through the Ryukyu Islands and Tsushima Straits on his way to the strait connecting the Sea of Japan to the Sea of Okhotsk. The 900-kilometre waterway has come to be known by a variety of names including the Gulf of Tartary, Tartar Strait, and, in Japanese Mamiya kaikyō (Mamiya Strait). An encounter with the Ainu people left little doubt that Sakhalin was an island, but La Pérouse decided not to risk the passage through the shallow waters. The waterway's Japanese name refers to an 1808 transit through there by Mamiya Rinzō, and the passage remained sufficiently obscure to allow a small Russian squadron to evade a British fleet during the Crimean War, utilising definite knowledge that was just five years old.

Interestingly, it was around this point, some two years out from Brest, that the first symptoms of scurvy. appeared/

Instead of passing through the strait, La Pérouse rounded the southern tip of Sakhalin on 11—14 August and passed north of Hokkaido in dense fog. He reached Petropavlosk in Kamchatka on 7 September for a planned stop to replenish his supplies. While he was there, new instructions from the Ministry of Marine in Paris pointed him towards Australia—specifically to Cook's New South Wales— where he was to investigate British activity. The orders also advised La Pérouse of his promotion to Commodore.

From Kamchatka, La Pérouse dispatched his interpreter, the young diplomat Barthélemy de Lesseps (uncle of the canal-builder), to return overland to Paris via St Petersburg, where his father was the French Consul-General, with accounts of the expedition's discoveries to date.

Turning south, the expedition then made for Botany Bay, travelling via Samoa, where a landing party from L'Astrolabe seeking water came under attack. The ship's captain, de Langle and eleven others died in the encounter, with twenty more wounded.

La Pérouse left without making any reprisals, called in at Norfolk Island without making a landing and arrived off Botany Bay on 24 January 1788.

Bad weather prevented him from entering the bay for two days and as he made his way in he passed Governor Phillip and elements of the First Fleet, who were in the process of switching their base from Botany Bay to Port Jackson.

John Hunter remained in the bay with the Sirius and some of the convict transports and supplied La Pérouse with what assistance he could. Under the circumstances, such aid was always going to be minimal, but La Pérouse to anchor established a camp on Botany Bay's northern shore, in the proximity of the Sydney suburb that now bears his name.

He maintained good relations with the English during his six-week stay but did not visit the new settlement at Sydney. La Pérouse's experiences there seem to have confirmed a view that the little that was known about eastern Australia did not justify too much attention. Favourable reports from Banks and Cook, it seemed, were seen as exaggerations to those who had taken them on trust.

Having provided the English with copies of his charts and taken advantage of returning convict transports to send further details of his activities back to France along with advice that he intended to explore the islands between New Caledonia and New Guinea and then pass through Torres Strait and reach Ile de France Mauritius) in December.

So, on 10 March La Pérouse sailed from Botany Bay and apart from a few false rumours, was not heard of for thirty—eight years.

,His disappearance prompted the French government in 1791 to equip a fruitless expedition under Bruny d'Entrecasteaux to investigate his fate, but though d'Entrecasteaux gathered some useful details on the coasts he encountered, La Pérouse's fate remained a mystery

until 1828, when Dumont d'Urville located wreckage at Vanikoro, Santa Cruz, north of the New Hebrides.

In the meantime, details of the voyage as far as Kamchatka appeared as the four-volume Voyage De La Pérouse Autour du Monde (Paris, 1797), with three English translations published between 1798 and 1799. Another work, Fragmens du Dernier Voyage de la Pérouse (Quimper, 1797), seems to have been the work of Pére Receveur, a scientist on the expedition who died at Botany Bay on 17 February 1788.

While La Pérouse's expedition is often described as purely scientific, his instructions included 'Political and Commercial Objects' including investigations into the China fur trade, details of European commerce and possessions, and possible locations for French settlement that, more or less, amounted to espionage disguised under a banner of rational investigation.

Sources: Australian Dictionary of Biography; J. Dunmore 'Dream and Reality: French Voyages and their Vision of Australia'; Chambers Biographical Dictionary; Evan McHugh 1606: An Epic Adventure; O.H.K. Spate The Pacific Since Magellan, Volume III: Paradise Found and Lost, Felipe Fernandez-Armesto (ed.) The Times Atlas of World Exploration, Glyndwr Williams, Explorers And Geographers: An Uneasy Alliance In The Eighteenth- Century Exploration Of The Pacific; Wikipedia