You might rate The Sex Pistols andThe Clash more highly, but for Hughesy’s money the single most significant force that emerged from the late seventies punk/new wave explosion was the knock-kneed Buddy Holly clone who statrted skewering his targets on his first album and consistentlyl hits the bulls eye thirty-five years later.

Of course, your mileage may vary...

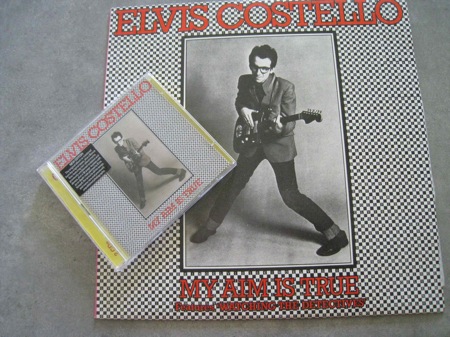

Rear View: Elvis Costello "My Aim Is True"

While his aim may have been true, what he was aiming for is possibly open to debate.

Regardless of the timing of the album's release and the fact that the label it was released on became associated with the punk/new wave movement, Elvis Costello was coming from the R&B/pub rock/The Band/Little Feat/Van Morrison end of the spectrum rather than the Sex Pistols/safety pin/torn T-shirt extreme.

It also seems quite likely that he saw My Aim Is True as his one and only shot at the big time. After all, there was nothing to indicate that thirty-four years after his debut album Costello would have parlayed a bunch of songs that, in his own words, reflected what was in his album collection at the time the songs were written into a discography that's bigger than many people's CD collection.

While My Aim Is True features songs that still feature regularly in Costello's live set (Red Shoes and Alison for example) there's still a fair chunk of what turned out to be inconsequential material there as well.

For another performer, or indeed another songwriter, the likes of Sneaky Feelings and Pay It Back may well have enjoyed repeated exposure in the set-list, but we're not talking just any songwriter.

Early publicity material suggested that Costello wrote a new song every day, and while that might not have continued as a long-term production rate, a glance at the man's vast back catalogue suggests that it wasn't too far wide of the mark.

You also can't help suspecting that there's a fair chunk of influence from The Attractions in there on the subsequent flurry of activity that produced This Year's Model, Armed Forces, Get Happy! and Trust in quick succession, with the country covers album Almost Blue thrown in for good measure.

All that lay very much in what must have been an uncertain future when Costello arrived to cut My Aim Is True backed by transplanted Californian country-rockers Clover.

Someone coming fresh to the album thirty-something years later will more than likely hear it for what it is - a collection of songs, some of them outstanding, others pretty good and the odd one that doesn't quite come off.

Fair enough, but that assessment, taken with a fair degree of hindsight, fails to take the times in which the album was released into account.

I know people keep banging on about a couple of classic eras of music, but unless you've been privileged to have lived through an era like the late sixties where every couple of weeks seemed to produce a new incandescent musical entity you're hardly likely to understand the ennui that had kicked in by the mid-seventies.

While Hughesy's financial and personal circumstances, taste for the grog and involvement with new non-musical interests were always going to cut back the rate at which albums were bought, the sheer simple fact of the matter was that when you went looking for interesting new stuff to listen to there wasn't much out there.

Much of that can be put down to the emergence of the album as the key ingredient in a band's recorded output.

Where continued economic or commercial viability had once demanded a new single every few months, it was now possible for some to get by putting out an album every couple of years.

When it came to studio time the tendency was to spend months working through various half-realised concepts where once you'd go in for a day to cut finished songs.

The punk rock explosion was one reaction to that situation, but from Hughesy's viewpoint it was one that came from the teenage noise end of the spectrum. Music, in other words, that was intended to get right up the nose of anybody outside the targeted demographic.

That doesn't mean you couldn't see and appreciate where they were coming from and why they were doing what they were doing but Anarchy in the UK didn't quite speak to a mid-twenties bloke in northern Australia in quite the same way it did to a teenager in a no-future English suburb.

If there was one development that had provided something worth investigating through the doldrums it had been the rise of what was termed pub rock in the UK and the emergence of a couple of R&B-tinged rockers in the States, people who seemed like they meant what they were singing about. People like Springsteen, Southside Johnny, Bob Seger and Mink de Ville, for example.

Given the nature of the beast, pub rock wasn't likely to throw up too much in the way of classic albums, tending rather to produce albums that represented more or less what was happening on stage but taken away from the live context there usually seemed to be something missing.

It was, more or less, a case of you needed to be there.

Costello, in his earlier incarnation as D.P. MacManus, had been on the fringe of the pub rock scene, but where most pub rock practitioners were musos looking for a paying gig, Costello always, from what Hughesy can make out, considered himself as a writer who performs rather than a performer who needs some material for the set-list.

Looking back on it, that's probably what made My Aim Is True stand out like a beacon back when it was released. It wasn't an album where everything worked, but it was a sign that here was someone several cuts above his peers whose future efforts would be well worth investigating.

As far as Costello’s attitudes to the music press back in the day the following very interesting quote comes from a Canadian magazine:

at that time. I was 22 and I’d just made a record, and there were two types of journalists that I encountered in the first days. There were people who looked like they’d escaped from a Glam Rock band and mostly comported themselves as if they were the rock stars, and in some cases they had every reason to believe they were, they were not bad writers and they’d probably taken more drugs than many of the people they were writing about. And then there were sort of leering, stained people with comb-overs and a cigarette with a long plume of ash, who were kind of like a caricature of a journalist in a bad movie with a belted raincoat and a spiral notebook who wanted sort of juicy tidbits about the girls that you met backstage. There were only two types of people. There was nobody that my youthful, arrogant self identified as a sentient human being. So I think I probably said things that I thought would get up their nose. And I think that worked. It mostly had the very, very pleasing effect of getting them to leave me the fuck alone for a number of years. And I got on and I made quite a lot of records in a short bit of time without the burden of having to speak to anybody.

Says it all, really....