It seems Steve Miller was, from the earliest stages of his career, determined to hit the big time, but it took a while. Many of us who were on board from the San Francisco era would be inclined to rate his early efforts above the later, gleaming airbrushed efforts like Fly Like an Eagle. But then, we would say that, wouldn’t we?

Rear View: The Steve Miller Band

In the summer of 1968 my family spent a week, a fortnight, I forget which at Bingil Bay between the time I sat for my Year Twelve exams and the publication of the results.

There wasn’t a great deal to do when you’d had enough of wandering around the beaches and rainforest apart from listening to the radio, and as it happened, the local radio station, Innisfail’s 4KZ, had a playlist with tracks that you didn’t hear anywhere else.

It’s the only place I recall hearing an obscure gem called Colonel Burke Has Pink Suspenders On, the B-side of a single by Peter Best, who went on to a career in advertising and film score composing. From what I recall the station hadn’t been on the air long and lacked the extensive record library that other stations would have built up over the years.

Given what they were forced to play as a result of that situation I wasn’t complaining.

In December 1968 two tracks receiving regular airings on the station were the Steve Miller Band’s Living In The USA and a wonderful bit of A.A. Milne-inspired psychedelia called Bears by the Quicksilver Messenger Service.

As a voracious reader of whatever music magazines I could lay my hands on, I was familiar with both names, having seen them regularly in print and knew that both came from San Francisco, and, while they weren’t as prominent as the Dead or the Airplane they were both significant forces in a thriving musical scene.

Beyond that, I didn’t know much.

I had no idea, for instance, that Steve Miller’s musical wanderings had taken him from Dallas Texas, where he was born on 5 October 1943, through Texas, Wisconsin and Chicago on his way to San Francisco, or that a member of the Miller Band was Boz Scaggs, who went on to temporary big name status a few years later.

With a driving harp-driven groove, Living In The USA was the first single off the second Steve Miller Band album released overseas the month before, although it took some time to make its way into a record collection near me.

Miller had been playing guitar and gigging, on and off with his mate Scaggs, from the age of twelve, with The Marksmen in Texas, The Ardells while they attended the University of Wisconsin and the Goldberg Miller Blues Band in Chicago, cutting a single (The Mother Song) for Epic before upping stakes and moving to the West Coast.

Along the way, the Goldberg-Miller Blues Band appeared on TV (Hullabaloo with the Four Tops and the Supremes), and gigged at a Manhattan club before they morphed into the Steve Miller Blues Band in San Francisco.

Signing to Capitol Records in 1967, the name was shortened to the Steve Miller Band and the first line-up, a quartet comprising Miller and Curly Cook on guitars, bassist Lonnie Turner and drummer Tim Davis turned up backing Chuck Berry at the Fillmore on what ended up as a live album. The band also cut three tracks to the soundtrack for the film Revolution, which also included tracks by Mother Earth and the Quicksilver Messenger Service.

But Miller, who’d learnt guitar from Les Paul, had ambitions that went beyond backing Chuck Berry and the odd contribution to movie soundtracks. There’s a little quote in Pete Frame’s Rock Family Trees that’s worth citing here:

I knew I couldn’t miss. The Dead and the Airplane barely knew how to tune up at that time - the big highlight was playing In The Midnight Hour for 45 minutes. It took me no time at all to put together a band that could play 25 songs - in tune and tight.

That’s a rather interesting perspective, though I suspect Jerry Garcia and Jorma Kaukonen might have taken umbrage at the barely knew how to tune up.

The quartet expanded with the addition of Jim Peterman on keyboards, appeared at the Monterey Pop Festival in June 1967. When Curly Cooke departed to join AB Skhy, Miller recruited his mate Boz Scaggs, fresh from a stint as a folk singer in Scandinavia and set off to record their first album, Children Of The Future, at Abbey Road Studios in London.

As noted in the Quicksilver Messenger Service Rear View, Capitol, having missed the first wave of San Francisco bands were inclined to be generous to those they signed, and Miller’s contract specified that they’d get to record at Abbey Road with a name producer, Glyn Johns.

Unfortunately, despite Miller’s ambitions, the album failed to attract attention when it appeared in May 1968, though when the follow-up, Sailor, appeared in October it climbed the Billboard charts as high as #24. Not bad, perhaps, but things could definitely have been better.

Almost as soon as Sailor was finished, Scaggs was off, apparently due to the ubiquitous creative differences. Peterman departed as well, and the band continued working live as a trio, adding mates such as Nicky Hopkins and Ben Sidran (who’d been a member of the Ardells back in Wisconsin) on keyboards in the studio.

1969’s Brave New World, again cut in England featured a guest appearance by Paul McCartney (aka Paul Ramon) on My Dark Hour and made it as high as #22. Later in the year Your Saving Grace made it to #38, then 1970’s Number 5 hit #23 before the wheels, more or less fell off.

A broken neck in a car accident put Miller out of action for a while, and gave Capitol Records an excuse to release Rock Love in 1971, an undistinguished mixture of unreleased live performances and studio material. By that point I was a confirmed fan but it seemed like a case of diminishing returns over time.

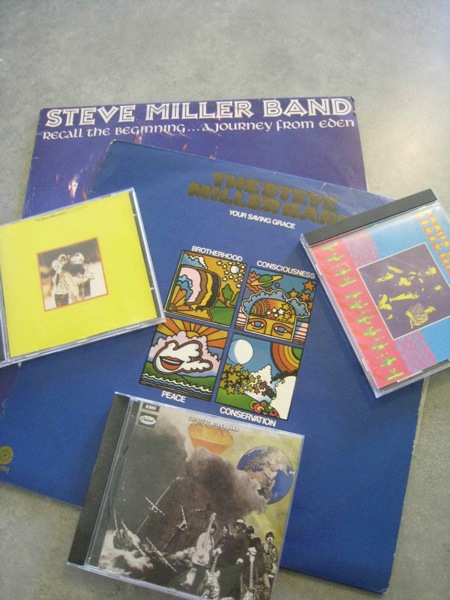

On the basis of Rock Love I was quite ready to write Miller off, but Recall the Beginning... A Journey From Eden was a welcome return to quite sublime form. For some reason the album never came out on CD, though there it is, large as life, in the iTunes Music Store. Go figure.

Readers who are familiar with Steve Miller’s work probably know it from one of the succession of albums and singles that followed The Joker in 1973. The single hit #1 in the States and the album was certified platinum.

Three years later, Fly Like An Eagle delivered three hit singles: Take The Money and Run, Fly Like an Eagle and Rock 'N Me, and the following year Book Of Dreams, Jet Airliner, Jungle Love and Swingtown kept the money rolling in, but by this point I’d more or less had enough.

Albums like 1982's Abracadabra were pleasant enough ear candy but I couldn’t see the point in shelling out hard earned that could be invested in other directions on music that, regardless of the number of copies sold, seemed like a pale echo of the early Steve Miller Band albums.

So what was it about those first four albums that was so good? Let’s go back and do a track by track, album by album Rear View.

A few preliminary observations first. A glance at the writing credits on my hard copies of the first three albums reveals that while Miller gets the most writing credits, Scaggs made significant contributions and once he was gone Brave New World’s nine tracks include four co-writes with Ben Sidran and contributions from drummer Davis and bass player Lonnie Turner to go with Miller’s three solo writing credits.

From the remark quoted earlier, it seems obvious that Miller had definite ambitions and when those ambitions failed to materialise he kept tinkering with the formula in the expectation that success would come eventually.

That’s fine in its own way but it isn’t likely to produce something that works on an artistic level the same way that Recall The Beginning... did, and it’s fairly obvious that, given a choice between artistic success and dollars, Mr Miller will go for the latter rather than the former.

In other words, if Children Of The Future and Sailor didn’t race to the top of the charts then it was time to change things around until you came up with something that did.

So, what about those early albums? How do they measure up in the cold hard light of the twenty-first century, even if there is a hint of misty-eyed nostalgia in there?

After the flurry of effects that opens Children of the Future you might be expecting that you’re in for something mind-blowingly psychedelic, but given Miller’s remarks quoted earlier, it shouldn’t be too much of a surprise to discover a fairly short, snappy up-tempo three-minute title track with the vocals cutting back and forth between Miller and Scaggs that crossfades into snippets of Pushed Me In To It (0:39) and You’ve Got The Power (0:53).

Those two tracks are no longer than they need to be, based on a single repeated pattern, pure pop without psychedelic trimmings, simple and simple, elegant and accessible.

Another crossfade, and the tempo drops back with strings behind Peterman’s keyboards on the Miller-Peterman In My First Mind, seven and a half minutes that may well have been meant to be listened to with the aid of artificial enhancements, but works well without them.

There are incomprehensible voices in the background, a door closes, and we’re into blues guitar that fades into crashing waves and layered vocals in The Beauty of Time Is That It’s Snowing (Psychedelic B.B.), a sound montage with the lyrics from the title track coming back in layered vocals to end Side One of the vinyl version.

One imagines these tracks performed in live performance with turn on a pin accuracy, and the set-list from 27 April 1968 show at the Carousel Ballroom reveals:

Children Of The Future - Prelude > Children Of The Future > Pushed Me To It - Vamp > Pushed Me To It > You Got The Power > In My First Mind (part 1) > In My First Mind (part 2) > Children Of The Future (reprise) > Beauty Of Time Is That It's Snowing (psychedelic B.B.)

That show, the middle of a two- or three-night run at the Carousel, seems to be the only known time that the first side of Children of the Future was played (more or less) in its entirety. A glance at the recorded-concert listing at Wolfgang’s Vault reveals nothing before 1973, a pity, since it would be interesting to see how the band handled the transition from the recorded versions to the stage.

Side two starts with acoustic guitar and harpsichord for Scaggs’ Baby’s Callin’ Me Home. It’s a pleasant little number with delicate touches, simple straightforward lyrics and a timeless charm. There’’s an up-tempo fade in that takes the listener into Steppin’ Stone, another Scaggs contribution with a chugging rhythm and interesting guitar lurking behind the vocal, and one of the albums relatively rare guitar solos.

Steppin’ Stone segues nicely into Miller’s Roll With It, which in turn morphs into another up-tempo number, Junior Saw It Happen and a cover of Fanny Mae before the tempo drops for a languid Key To The Highway with lazy harp and delicate organ from Peterman.

What’s on display is a tight rhythmic musical unit turning out interesting music without instrumental frills or extended solos, which probably raised their heads in live performance. The result, far from the full-on psych-out you might have expected, is tasteful sixties pop of a very high order, an almost seamless whole where the album is more than the sum of its individual parts.

Unfortunately, despite the presence of a number of tracks that may have worked well in a commercial radio format it failed to sell massive numbers, possibly (at least this is Hughesy’s theory) because the individual tracks didn’t work as well away from the context of the album.

Regardless of sales, Children of the Future was an impressive debut effort, and the first side of the follow-up, 1968s Sailor, is another exploration of the same musical territory.

There aren’t many albums where the first two minutes consist of fog horns over a gradually swelling instrumental background, but Sailor is one of them. The sound effects in Song For Our Ancestors give way to moody atmospherics, a little percussion bubbling under a guitar and organ that weaves its way through a fairly straightforward theme.

There’s a short burst of drums before Dear Mary, a soft slow ballad with delicate breathy vocals from Miller. Classy chamber pop, understated, refrained and quite lovely in its own right, with a little trumpet and guitar passage at the end that gives way to the album’s first rocker, My Friend, written by Davis and Scaggs, sung by Miller. Clean guitar, driving drums, a passage of handclaps that takes the listener into the first heavy guitar on the album.

That’s replaced in turn by the sound of a motorcycle, a driving beat and harp solo at the start of Living In The USA. The organ comes in, along with a breezy vocal as Miller offers socio-political observations: Dietician, Television, Politician, Mortician... mightn’t be the sharpest bit of cultural commentary ever written but the Somebody give me a cheeseburger! at the end of the track says it all, really. You want fries with that?

Side Two kicks off with Miller’s Quicksilver Girl, a saccharine tribute to Girl Freiberg, teenage bride of Quicksilver Messenger Service’s bassist. Pleasant enough, but although it's pretty it is also pretty lightweight.

On the other hand if you skip it you don’t get the contrast as a little acoustic guitar lick leads into Peterman’s Lucky Man. Keyboards, high harmonies behind the lead vocal and prominent drums before assorted hipster voices take us into Johnny “Guitar” Watson's Gangster of Love, slurred vocals from Miller that turn into a chortle as Miller expounds his prowess as a lover and before you know it you’re into Jimmy Reed’s You're So Fine, the album’s excursion into the blues with tasty harp and guitar work.

There’s a floating intro to Overdrive, written and sung by Scaggs over a chugging semi-Bo Diddley beat, with tasty slide licks in there as well. The lyrics aren’t the greatest philosophical statement you’ve ever heard, but there you go.

The killer punch comes with the album’s closer, again written by Scaggs. Dime-A-Dance Romance is a solid rock and roll invocation of the joys of the dance that presumably would have gone down well in the dance halls. Come on honey, Scaggs entreats, we’re bound to make it. It’s the high point of an excellent album that isn’t quite what you might have expected.

Internal tensions, however, meant that by the time they were back in the studio to record the third album, 1969’s Brave New World the Steve Miller Band was a trio with occasional keyboard help from Nicky Hopkins and Ben Sidran.

In line with the power trio configuration the softer elements on the first two albums are gone, and even the delicate touches come with a harder edge. After all they’re on their way from a dream of the past to a brave new world as the album’s leadoff track explains, where nothing can last that comes from the past.

Actually there’s quite a bit from the past lurking behind that harder edge.

The title track comes first, a three and a half minute statement of intent, high harmonies behind Miller’s vocal, a jaunty opener with precise instrumentation. That’s followed by Celebration Song with the high sha-la-sha-la-la-la-la’s as Miller informs that the listener’s in for a good time since the band is gonna play. Maybe they’re not the greatest lyrics you’ve ever heard but they fit the vibe. Paul McCartney’s lurking in the background there as well.

Things move up-tempo for Can’t You Hear Your Daddy’s Heartbeat? underpinned by a surging bass line and slick overdubbed guitar work from Miller. Got Love ‘Cause You Need It keeps the jaunty up-tempo thing working, but there’s a touch of menace lurking behind the singer’s message.

Guitar and tasteful piano launch Kow Kow, and while the lyrics are nonsense - seriously, Miller’s never likely to threaten anyone’s position in the list of Rock’s Thousand Greatest Lyricists - but there’s a wonderful little touch in the turn on your love-light middle break that leads into a nicely ranting conclusion before a piano and organ play-out from Hopkins and Sidran that’s nicely restrained. A great track, lyrical nonsense notwithstanding.

Seasons isn’t the greatest philosophical statement you’ve heard either, but there’s bright acoustic guitar prominent in the mix

Arguably the closest to a potential hit single on the album, Space Cowboy is another classy track, nicely put together with plenty of interesting touches bubbling under the surface. There’s a strong beat from drummer Davis and a buzzing bass line from Turner-and the main guitar riff has a touch of the Lady Madonnas about it.

The quirky lyrics are back for bassist Lonnie Turner’s LT’s Midnight Dream, along with some tasteful acoustic slide picking and the high harmonies back in the mix. Solid.

There’s a fairly funky drum intro to My Dark Hour, quite possibly the work of a certain Mr McCartney, who’s credited as contributing bass, drums and vocals - that’s certainly him in the scream over the play-out, no one else in rock at the time had quite the same scream - and the riff turned up gain on Fly Like An Eagle a few years later.

All in all, Brave New World is another solid album of classy rock-tinged pop music, and it’s the third in a line of albums that seemed to offer a little more as each one slipped out into the market. The band is tight, the writing credits are shared around (three to Miller, four to Miller/Sidran, one each to Turner and Davis) and the production work (from Glyn Johns) adds a pleasing veneer over the top of the mix.

Given the fact that the core trio of Miller, Turner and Davis had been together for getting on to three years, you’d expect them to have their act together, and you’d have thought that success was a matter of time, yet, somehow the release of the fourth album Your Saving Grace passed unnoticed.

Arguably, the fourth album is the pick of Miller’s early work.

Listening to it again after a gap of a good ten years it’s astounding how good it is. A fair bit of that is the much more prominent role occupied by Hopkins’ piano, but it’s the work of a band that’s really hitting its straps.

And, until a call to the local radio station for some phone-in competition, or whatever, until the source from which my mates and I had picked up a number of very reasonably priced albums, I was completely unaware of its existence.

More than likely it just slipped by under the radar - Miller and Co. never had much of a profile in the U.K. and Rolling Stone, the most likely source through which we’d have been apprised of the album’s existence, was a hit and miss affair in the distribution and circulation departments as far as Queensland was concerned.

More than likely the Sunday Truth had detected the presence of long-haired hippie free-love dope-smoking propaganda on the news stands again. They tended to be big on that kind of thing.

In any case I negotiated a reasonable price and a couple of days later found myself sitting down to digest another Steve Miller Band offering. That happened close to forty years ago, so perceptions may have changed over the years, but from the opening Little Girl to the concluding title track it’s definitely up there with the best of the preceding three albums.

Little Girl, while straightforward in the lyrical department is full of instrumental nuances and inflections that are several thousand kilometres removed from Miller’s later more-or-less boogie-by-numbers. Could have been the sort of single that’d add a touch of class to the charts and while you wouldn’t have expected it to sell millions could have added a bit of light and shade to the Top 40.

Even better is Just A Passin’ Fancy In A Midnite Dream, a Miller/Sidran composition with a surging beat behind a throaty vocal from Miller.

The tempo picks up with Miller’s Don’t Let Nobody Turn You Round, largely drum-driven, with a touch of the call and response about the vocal line, which again mightn’t be intoning the most philosophical analysis of society you’ve ever heard but it works.

Baby’s House, a Miller/Hopkins co-write, provides a welcome change of pace largely built around layered vocals, Hopkins’ piano and Sidran’s organ with nice echoes of the slower material off the earlier albums. Clocking in a tad under nine minutes, it’s magnificently understated.

I’ve heard plenty of versions of Motherless Children over the years. Clapton’s riff-driven offering and Jeff Lang’s up-tempo cover are two favourites that spring to mind. Miller slows it right down, keeps it simple and the result works as well as any of the others and better than many more formulaic versions. Electronic touches. tinkling harpsichord and tasteful guitar work from Miller, demonstrating that he can play. As in so many cases the secret isn’t in the notes you play but in the ones you leave out.

Turner’s The Last Wombat In Mecca doesn’t have any obvious links to Australia or Islam, but does feature some tasty acoustic guitar. Beyond that I haven’t got a clue what it’s about.

The album starts to build up to a memorable end with Miller’s Feel So Glad, pushed along by Hopkins’ stately piano runs behind Miller’s heartfelt vocal. Deceptively straightforward.

Finally there’s the title track, written by Davis, where a swirling organ and strummed acoustic introduction switches to a spooky echoing spoken passage, which in turn turns into an uplifting extended play-out bringing a classy album to a classy conclusion.

After four quality albums I had high hopes for Number Five. Unlike the current situation where news of forthcoming releases is flashed around the internet, followed by a wave of discussion, speculation, analysis of leaked copies and so on, there was nobody around to sound the warning bell when it transpired that Glyn Johns had been eased out of the producer’s chair and Miller had eased himself into it.

Apart from that, on the surface the only obvious differences between Number Five and its predecessor was the sharing of bass duties between Lonnie Turner and Bobby Winkelman and a bit of harmonica from Charlie McCoy. The writing credits looked much as before with a track from Winkelman and a Miller/Scaggs collaboration, but the album was, in a number of ways, a major disappointment.

Given the fact that there wasn’t much variation in the other elements one wonders whether the departure of Johns was the major factor. The fact that it was the fifth album they’d released between April 1968 and June 1970 may also have something to do with the matter. While I haven’t listened to the album in years, even at $10.99 I’m not in a hurry to buy a copy from the iTunes store and lack of an operational turntable means that the vinyl copy isn’t going to get a workout any time soon.

Basically, after a couple of listens I filed the vinyl away and waited to see what came next. I wasn’t quite ready to write Miller off, but at the same time I was starting to have some serious reservations.

I think I heard the following album once. In fact I may well have failed too get all the way through the first listen to Rock Love. A mixture of pretty live and studio recordings, the album was almost universally condemned, and if I went as far as buying a copy it was long ago consigned to a second-hand store. It’s certainly conspicuous by its absence from the vinyl collection, and if I’m disinclined to pay $10.99 for Number Five, there’s no way I’m shelling out $17.99 for Rock Love.

From the opening bars of 1972’s Recall The Beginning...A Journey From Eden all was, however, forgiven. Welcome is a snappy little instrumental, the sort of thing you’d expect a soul revue to kick off with, nothing outstanding in itself but the playing is crisp and it grooves along nicely.

Handclaps and ooh aah vocals lead into Enter Maurice, a wonderful little slice of doowop. Always had a soft spot for the old doowop, and there was a bit of a revival at the time. It mightn’t have been the stuff of the earlier albums (but then again Sailor featured Gangster of Love, which wasn’t a million miles removed from the vibe here). In the space of two tracks much of Number Five and all of Rock Love was forgiven. A false, finish, and there’s Maurice back again, little cries from his lady friends, and a slightly more chilling ending.

The tempo drops right down for High On You Mama, slinky slide underpinning a laid back groove. After the sonic mess that prevailed on the previous two albums (again, I suspect that the change in the producer’s chair had something to do with that) the sound is crisp and clear with warm vocal harmonies. Nice.

Heal Your Heart starts with a loose-limbed groove, a harbinger of some of the things to come, and while it’s not my favourite track, I wasn’t skipping past it in a hurry. The Sun Is Going Down is nothing out of the bag either, but a pleasant enough listen.

Side One of the album sees the groove from Welcome back as Somebody Somewhere Help Me, an up-tempo blue-eyed soul number that brings the side to a snappy finish. While it wasn’t as consistently great as some of the earlier work the side could comfortably filed under Welcome Returns To Form.

The second side starts as warm acoustic guitar, whispered vocals, swirling strings lead into Love's Riddle. What do you do when your love is untrue ... isn't an original question, but it’s a theme that has been mined consistently through the years.

The start of Fandango continues the same feel before an up-tempo middle section lifts things out of the low down feeling that had prevailed for the preceding four and a bit minutes, which is quite long enough for that sort of thing to last. A couple of dramatic chords and we’re back to the whispered vocals. It’s a pleasant exercise in contrasts.

A swirl of strings and finger-picked acoustic guitar leads into Nothing Lasts. As usual with Miller’s lyrics the words aren’t too deep, but the message is stated fairly simply and if they’re a string of sentiments you’ve heard many times before, maybe that’s because they’re describing something that most of us have felt at some time. There’s a tasteful call and response element in there as well.

The album closes with Journey From Eden, a ballad that works in some of the same ground Miller was mining as far back as Children of the Future. Again, while the lyrics aren’t going to end up in an anthology of Rock’s deepest poets, if the point of the exercise is to create something that people can identify with without travelling too far into navel-gazing Miller succeeded reasonably well for mine.

Like most of its predecessors Recall The Beginning.... didn’t have too much impact on the charts. I’d been sufficiently enthused by the album to line up for The Joker and Fly Like An Eagle when they came out, and the successes Miller had with the next couple of albums was enough to seal his future direction.

Unfortunately, given events in London and New York in the late seventies, that wasn’t a direction I was keen on following.

In the Top Thousand:

Children of the Future:

Children of the Future

In My First Mind

Sailor:

Living In The USA

Gangster Of Love

Overdrive

Dime A Dance Romance

Brave New World:

Got Love ‘Cause You Need It

Kow Kow

Seasons

Space Cowboy

My Dark Hour