Across the Nullarbor

It might seem strange to learn that one of the highlights of the Indian Pacific experience was several hundred kilometres of virtually nothing, but we'd been told that was the way things were before we hit the Nullarbor, and actually there's nothing I can think of that would prepare you for the discovery that several hours of a 360-degree vista where the horizon is totally unencumbered and uncluttered by protrusions of any kind is an enjoyable experience.

At 6:00 when the wake up call and the cups of tea and coffee arrived, that was still all before us and we had little real idea of what was in store apart from a very long stretch of unbending railway track.

Since the sun wasn't quite with us and the cabin only delivered a view to the left, the Club Car, with views to both sides seemed the way to go, and we arrived to find the place surprisingly packed with people obviously there in anticipation of the Red Service call for breakfast since the area emptied remarkably quickly when the call arrived.

The breaking dawn brought a misty sun over low scrub and red ochre sand hills, that rich red orange almost terracotta on steroids, with small trees scattered across the landscape. There wasn't much that was too high. With the sunrise shots taken and no one nearby to chat with, a move back to the cabin and a visit to the Rain Room seemed like a good idea. There wasn't much to see, those things would have to be done eventually and the future was an unknown quantity.

I'd emerged and dressed for breakfast, and was in catch up mode on the field notes while Madam showered when my trusty slim HBSP pen decided to give up the ghost. Fortunately I had a spare, but a brief grapple with the alternative wasn't entirely satisfactory, so I headed off in search of a substitute, investing $2 on an Indian Pacific el cheapo that wasn't much chop. Any subsequent decline in reportage can be attributed to the change.

Poor workmen, their tools and all that…

Madam emerged, dressed, and expressed a desire for further rest so I set off with pen and notebook thinking that there'd be space in the Club Car and I'd be able to continue composing without seeming too unsociable. After all there'd been no one in evidence a mere ten to fifteen minutes before.

It's remarkable how quickly things change.

I arrived to find all available seating occupied except for a stool near the bar, and it was obvious that solitary scribbling was setting the scrivener apart from the rest of the population. I gave up and looked around to discover that the mist had closed in and turned into fog, not quite your pea-souper, but enough to prompt the hospitality manager to remark that it was something she hadn't experienced on this leg of the journey before.

Up to this point we'd been sitting in the cabin till the meal call came over, but it seemed like gathering in the Club Car was the standard modus operandi so I wandered back to the cabin to suggest that Madam might care to join the throng. She did, but the joining lasted all of ninety seconds before the chime came and we were off to be seated for breakfast.

There isn't much room for variation in the cooked breakfast department and I went for the standard option, choosing poached rather than scrambled, eggs to go with the bacon, chipolata, mushroom and tomato. We were in the middle of ordering when the fog lifted, as if by magic, and we found ourselves gazing at the awesome extent of the Nullarbor in all its glory.

The other couple at the table, a farmer from the Blue Mountains and his born to shop for shoes missus were a mine of information since he was a Sandgroper by birth and had made the crossing several times by both road and rail. His better half wasn't at her best in the morning person role, but this was new ground to her so there were questions, remarks and bits of repartee flying across the table as we moved further onto a vast and seemingly unchanging landscape.

When I spotted something that could have been mountains I was informed that it was probably cloud and there was nothing out there to the south from the railway track to the highway, which lies a hundred kilometres away and beyond that to the Great Australian Bight. Nothing.

Not a hill, valley, river or anything that might deliver a drop of variation to a dead flat and even horizon.

There was no variation on the northward side either, and as the PA announcement advised that we'd embarked on the world's longest stretch of straight line rail I meditated on the fact that on a full-circle vista there was nothing to break the absolute dead flatness of the Nullarbor skyline.

That lack of variation gave me plenty of time for catch-up scribbling, since there was absolutely nothing new that could be added in the way of interesting detail apart from a mercifully short half-hour stop at Cook.

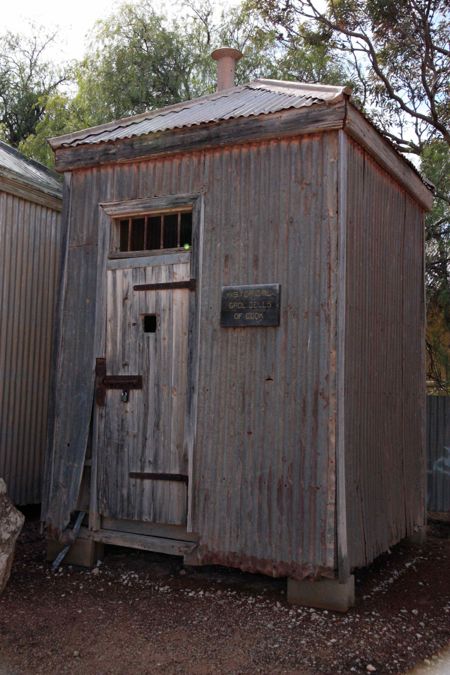

You wouldn't want to be spending more than thirty minutes at Cook, which dates back to the construction of the line during the First World War.

Named after the sixth Prime Minister of Australia, Joseph Cook rather than navigator James. These days Cook is effectively a ghost town since the railways were privatised in 1997 and the new owners didn’t want to maintain a community that would increase overheads without contributing to revenue. As a result the hospital and the school are closed, though there is still evidence, in the only substantial clump of trees on the Nullarbor, of attempts to create an oasis in the desert.

There are still refuelling facilities and overnight accommodation for train drivers, but the main purpose for the halt is to replenish the water supply for the Indian Pacific, originally done with water drawn from the Artesian aquifer but now, in the cause of greater profitability, with water brought in by train.

The population has declined to either three or four, not that we managed to sight any obvious locals as the passengers of the train wandered around the deserted buildings. Most of them were presumably engaged with the store, which opens while the train is in town. We took a clockwise circuit around the outskirts, getting a good look at what remained.

Madam's photographic interest drew her away from the crowd, and as I watched and waited I found my imagination moving into Hercule Poirot Murder on the Indian Pacific territory. Over the next week and a bit I managed to put together a workable plot line, but it's one that'll have to wait its turn in Hughesy's queue of fiction projects.

We were back on the train soon after the blast on the town's fire siren signalled an impending departure, and once we'd set off and signs of human occupation were gone I found myself pondering matters metaphysical.

There's a line in a Fred Dagg monologue about the Australian novel referring to the stark hostility of the very land itself, a line that draws its inspiration from fictional descriptions of an environment that doesn't offer room for the niceties of a comfortable suburban existence.

Alternatively, you could wax poetic along the Dorothea Mackellar I love a sunburnt country lines, but out here that doesn't really wash either. Concepts like beauty, in the sense of being attractive to look at, go out the window. Although the stark hostility of the very land itself may be going over the top just a little, as the train continued through a landscape that relentlessly refused to offer any variation whatsoever, I decided that it wasn't so much a case of hostility as a supreme indifference to the day to day existence of humans and other life forms.

It's there. It's always been there, and for a long time it's been just like this and it'll still be like this long after Madam and I and the other occupants of the train and all their descendants are gone.

There's a sense of timeless indifference and if I hadn't been in the middle of an all-Australian playlist on the iPod I could have gone for repeated replays of Warren Zevon's The Vast Indifference of Heaven, though here it wasn't heaven but the vast, empty and unchanging earth.

The straight stretch ended at Nurina, some five hundred kilometres and six or seven hours after it had started during breakfast time, but the landscape continued to refuse to incorporate a vertical dimension.

Shortly afterwards we passed the site of an old prisoner of war camp, and a little further on at Rawlinna we stopped and a couple of stockpiles from the nearby limestone mine provided a break from the unrelieved flatness, though some six hours after we came into the Nullarbor there was still no change on the skyline.

That’s not to suggest there was nothing that caught the eye, particularly at the stops to pick up a station mail bag halts, seemingly in the middle of nowhere. At one of them, around lunchtime, Madam’s eye was caught by colourful patches of red wildflowers, while a bit further along she sighted a solitary cow moving steadily towards the stationary train as if intent on making a rendezvous.

At least that was the way it seemed from where we were sitting.

After some time, however, the vegetation started to gain a little height and before long we found ourselves in scrub high enough to cut off the view to the horizon, though I didn't note much in the way of intervening hills until the Blue Service was called for dinner and I repaid the previous night's shout with a decent bottle of tempranillo.

Dinner time took us into Kalgoorlie, and with a three hour stop scheduled there was nothing for it but to hoof it around town for a while, an endeavour that encouraged by a significant diminution of the on-board hospitality.

Throughout most of the journey, with the external doors secured, there was little need to lock cabin doors and so on, but with the lengthy train stationary on the outskirts of a substantial city there was the possibility of petty larceny and other forms of mayhem, so once the train had been divested of its passengers it went back into lockdown with two doors and a similar number of hospitality outlets open.

It doesn't take three hours to walk round downtown Kalgoorlie, and temptation to roll into a convenient waterhole, sink a couple of beers, then return to the train with replenishments probably accounted for the warning that bringing grog onto the train was verboten, something that hadn't been mentioned when I looked at the possibility of bringing a couple of bottles of wine with me for the purposes of in-cabin consumption.

Kalgoorlie presented as a town that had done very well for itself thank you towards the turn of the previous century, with buildings of a similar style to those we'd sighted in Broken Hill. There weren't many locals out on the streets, and while that was more than likely a function of the hour on a Monday night (ten o'clock on a Saturday evening may have been a different matter) I suspect the modern mining twelve hours on, twelve hours off, alcohol and substance testing rigidly enforced ethos was a significant factor.

A series of commemorative pavers revealed Kalgoorlie as the birthplace of Walter Lindrum, the Bradman of the billiard table, and a number of other sporting identities, most of whom none of our party had ever heard of. Given Madam's background that was hardly surprising but many of them were footballers, Gavin and Lynn were from Victoria, and we were presumably talking AFL. It seems footballing fame didn't necessarily spread eastwards in the pre-Eagles and Dockers era.

I was also quite taken by the wording on this delicatessen store front. Presumably, in the owner’s mind, classification as gourmet precludes the culinary traditions of Italy and South Africa. Now, there may be a case for the latter, but Italian?

Having negotiated our way back onto the train the ladies made their way to the cabins while Glen and I headed for our Club Car in the vain hope of finding it open for business.

We were about to call it a night when we were joined by a young bloke I'd sighted with a camera and tripod at various junctures over the preceding few days. He'd been carrying a copy of Uncut magazine just before we'd gone in for dinner, and a brief conversation revealed that he, like Hughesy, was a regular reader of Mojo.

After Gavin called it a night we sat discussing musical matters for a good hour before I decided that uncertainty about what lay over the horizon in Perth meant that it wasn't a good idea to continue sitting up and talking music. Still it was one of the most enjoyable conversations I've had for many a year.

Talking Derek Trucks, Little Feat, Captain Beefheart and Forever Changes with a young bloke in his twenties or early thirties on the Indian Pacific. Who'd have thought?